Positive Train Control (PTC) is an ever evolving system, one that has seen many reinventions throughout its history. From 1920s where systems to automatically stop a train were first created, to now where PTC looks more like the technology of self driving cars, it has improved greatly. However, for such a helpful and safe technology, PTC implementation has seemed to some a knee-jerk reaction, a reaction that should have been forcibly mandated earlier than 2008. Many experts say that PTC has suffered from the quick turnaround deadline Congress has placed on railroads, stymieing progress in improving the technology of PTC in order for deadlines to be met. It’s like a college kid who waits until the night before to read and write their final essay on War and Peace, they may get the gist of the prose but they’re not going to be shedding any new interpretations on the classic novel.

Before the 2008 Chatsworth crash, there were mandates from the 1920s in place to have some sort of PTC technology installed on tracks and locomotives. However, these mandates were, to quote Pirates of the Caribbean, more like guidelines. The very first mandate was the Esch-Cummins Act, a federal law that returned railroads to private operation after World War I, albeit with regulation. This law also granted the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) authority to consolidate railway properties and regulate shipping rates, mergers and acquisitions, as well as incorporate safety regulations. The ICC required 49 railroads to have an operating train-stop or train control system on high trafficked portions of their passenger train routes. While some implemented the technology, many did not use it, especially since the technology was constantly changing. In the 1980s, the first advanced train-control system was created using digital radio communication, and in 1987 a similar technology was created using GPS. Many rail properties began creating their own technologies, but with no concrete direction from the original law, such as “The train-control must prevent the following and be interoperable…” the regulation became a check in the box as opposed to an actual safety measure. In fact, in 1990 the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) counted PTC among its “Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements.” Nothing works better than asking Santa for safety improvements, right?

Fast forward to 2008, where a distracted train engineer runs two red signals colliding full speed with a freight train causing the deaths of 25 people and countless injuries. Within one month of the incident, Congress had enacted the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 to improve rail safety by, most notably, requiring PTC to be installed on most of the U.S. railroad network by December 31, 2015. This was extended to December 31, 2018 after the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that major Class 1 railroads had taken great steps to install the PTC technology, but would need more time. The bill allowing the extension, also included the ability for railways to petition for another extension to 2020, as long as half their locomotives and tracks had installed PTC by the 2018 deadline. They may extend in one year increments after 2020 on a case-by-case basis.

There are many complexities to installing PTC, from integrating existing technology to ensuring all technology is interoperable. With the bill passed so quickly, and with such a tight deadline, especially given the monetary stress induced by said deadline, many people worry that the implementation of PTC was not thought out and is becoming another check in the box to appease a knee-jerk reaction. The bill in 2008 allotted 199 million dollars to be split between 43 railways, and currently states:

$925 million in grants to support railroads’ development and implementation of PTC systems

-

- $400 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funding

- $25 million in fiscal year 2016 Railroad Safety Technology Program funding

- $197 million in funding administered by the Federal Transit Administration under the FAST Act

The FAST act is shared by all ground transportation, the American Recovery Act is a stimulus package shared across the board, and the grant funding can only be used for very specific tasks. The technology to install PTC currently costs around 14 billion per railway.

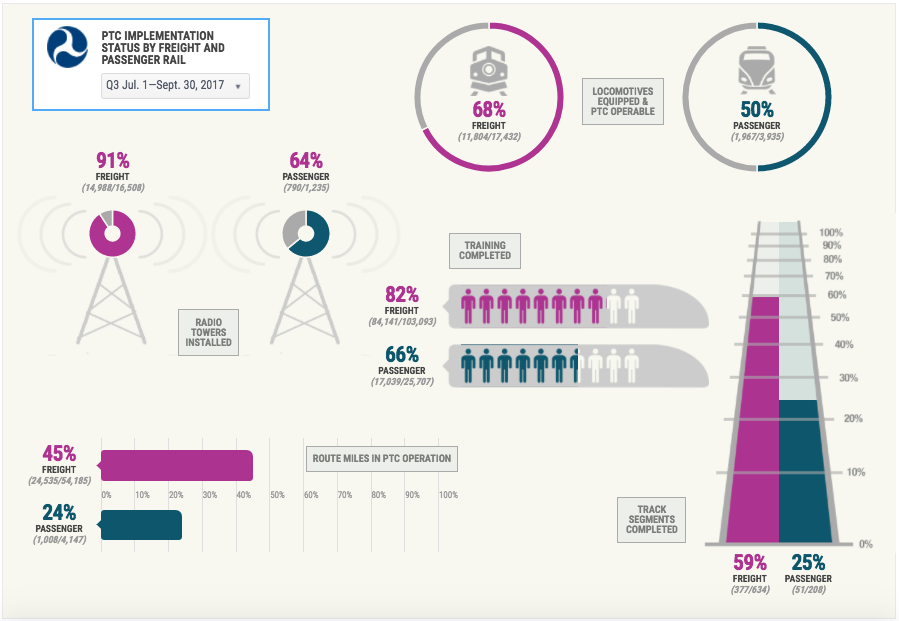

The scariest part about this whole process is, it’s 2018 and according to the Association of American Railroads (AAR), “The 2018 deadline [only] requires that all of the hardware and software must be installed and at least 50% of the route miles must be operable.” They also say that required testing software for PTC is not yet available. Below is an infograph of PTC’s progress in Q3 in 2017 courtesy of the Federal Railroad Administration.

Safety in our railway transport needs to be more strictly regulated, that is a fact. But legislation needs to be realistic about goals and admit that playing catch up this quickly puts more lives at risk.

Next time, rail safety overview and the final installment of the PTC series.